How local farms adapt and persevere during tough times

Nestled in a valley where vineyards and redwoods give way to green rolling hills is the tiny town of Freestone. While the world may know Sonoma County as “wine country,” out here, grass reigns supreme. Most mornings, a thick fog descends, replaced in the afternoon by a wind that trains the few scattered trees diagonally. Each year, with help from grazing animals and some of the most tenacious farmers around, the county’s pastoral grasslands produce 67,637,712 gallons of milk (according to the 2018 Sonoma County Crop Report).

Over the years, Omar Mueller, proprietor of Freestone Artisan Cheese, has watched older dairies struggle while many promising artisans have come and gone. In his small shop showcasing local creameries, the shifting selection of items in his display case tell a story that is at once about creativity and tribulation, loss and perseverance. Mueller spends his days behind the counter chatting up locals and visitors alike with the stories behind the cheeses, recounting the people, animals, land and traditions that shape each one.

But not lately. Mueller’s shop has been shuttered for nearly three months (at time of print). The COVID-19 crisis has taken its toll on local shops, especially those that depend on an influx of visitors to Sonoma County. Even worse for the dairy industry as a whole, with over 50 million children stuck at home, every school cafeteria in America has canceled their orders of those ubiquitous half pint milk cartons. Many dairy farmers, unable to pivot quickly enough, had little choice but to dump their milk.

But, the challenges facing the dairy industry started long before coronavirus. Over the past 30 years, 100,000 American dairy farms folded. That’s ten per day since 1990. Smaller operations have suffered most: those with less than a hundred animals declined more than 50 percent, while those with more than a thousand increased 50 percent. Last fall, amid the Trump administration’s trade war with China that jeopardized over 17 percent of total U.S. agricultural exports, Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue told a gathering of struggling small-scale dairy farmers, “In America, the big get bigger and the small go out.”

At its peak, Sonoma County’s pastureland boasted over 800 dairy ranches. Today, only 64 remain.

“I like to stay hopeful,” said Scott Bice, farm manager of Redwood Hill Farm in Sebastopol. “It’s not an easy business. But I love it and believe there’s still a place for smaller producers.” Scott and his family’s farm exemplify a small contingent of dairies that buck trends, starting with the animals. While 56 of Sonoma County’s 64 remaining commercial dairies raise cows, three tend sheep, one specializes in water buffalo, and four milk what are arguably the barnyard’s biggest personalities: goats.

The key to survival for Redwood Hill Farm has always been adapting, finding a niche and staying creative. But, says Bice, “Milk prices simply haven’t kept up with the rising cost of production.” This is especially true for Sonoma County, where skyrocketing land prices outpace the rest of the country. And where labor costs have not only increased but, because of immigration policies, the availability of foreign-born workers–the hardworking backbone of the industry–has fallen. Costly regulations, often applied the same to small family operations as they are to mega-dairies, can be crippling. And the emergence of milk alternatives, like soy, almond and rice, haven’t helped either.

Over 50 years ago, the Bice family, led by Scott’s older sister Jennifer, found a niche that allowed them to better control their own market. In a time when most Americans recoiled at the idea of goat milk, Redwood Hill began proving that these wily animals can produce healthy and delicious cheeses, yogurts and kefirs. Pioneering women like Jennifer and Laura Chenel–the goat women, as Bice calls them–as well as chefs like Alice Waters, cultivated a new appreciation for goat dairy products. The Bice family business steadily grew over the decades, and in 2015, the creamery was acquired by Swiss dairy cooperative Emmi.

The Sebastopol farm itself remains in the Bice family. Today, they milk 90 goats, supplying the creamery with raw product. But he knows that isn’t enough to get by. So Scott has grown his focus on breeding stock as well, naturally selecting the best traits from his award-winning herd and selling to farms across the nation and beyond, both online and at events.

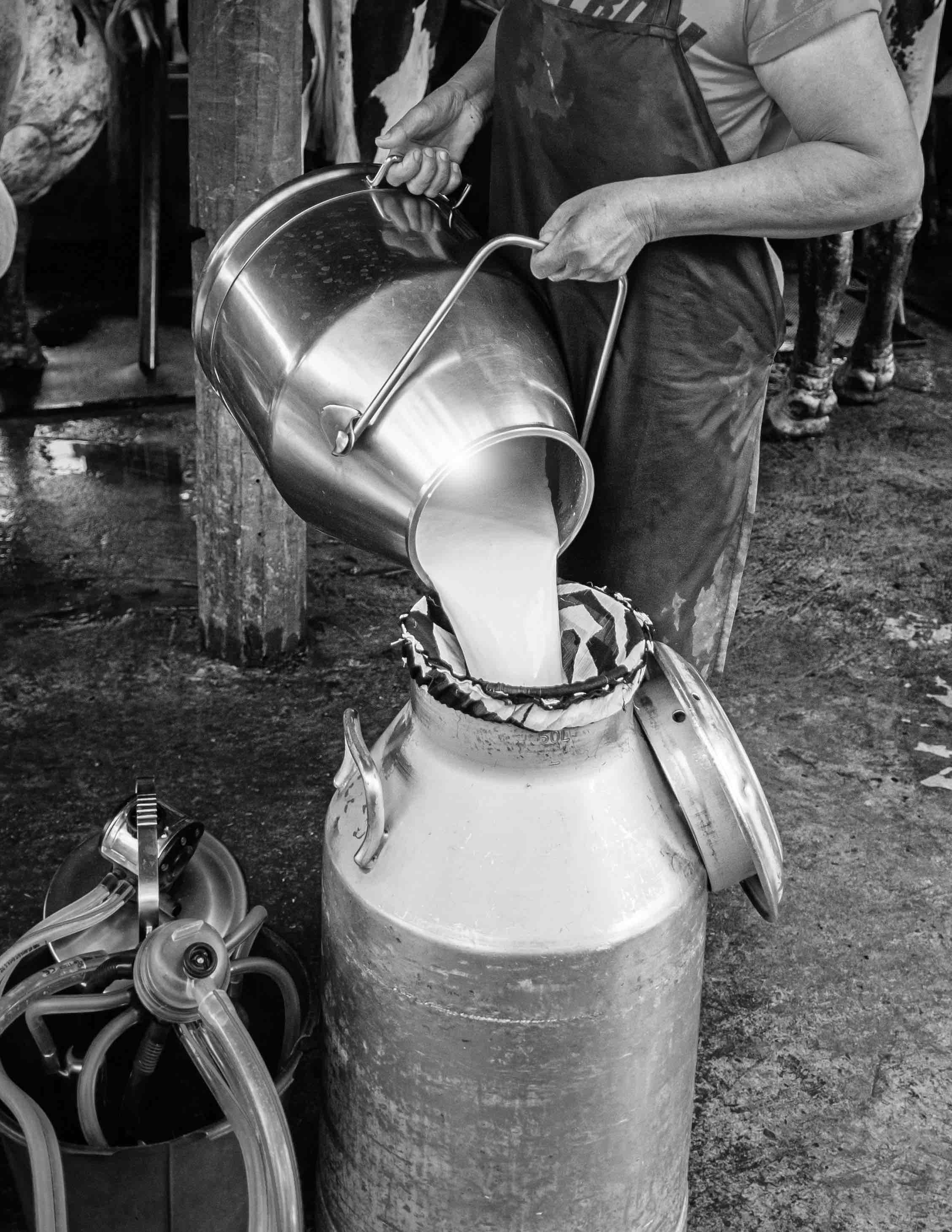

Farm tours round out the family’s business model, educating visitors about sustainable land stewardship and where their food comes from. COVID-19 has put tours on hold, but Scott is looking forward to reconnecting the community with his family’s land. “It’s worth seeing. When you operate at a smaller scale,” he says, “you really get to take part in every step of the process and develop holistic systems, from watching a birth to composting your herd’s droppings and using that to grow more food. Best of all, I get to know every single animal.”

Further south, between windswept hills near the town of Tomales, yet another of these “goat women” is Tamara Hicks of Toluma Farms. A relatively newer arrival to an industry where most businesses stretch back generations, she began by selling her raw product to Redwood Hill but soon pivoted to her own cheese-making. Then she decided to go one more step and vertically integrate from top to bottom.

“My husband is from New York,” said Hicks, “and he’s always said the Bay has the best cheese and the worst bagels. So we’re trying to fix that.”

Last year, Hicks and her team opened up The Daily Driver, a bagel bakery and creamery located in the Dogpatch neighborhood of San Francisco. “I wanted a business where my staff could evolve, bring their own ideas and become partners. It’s really the only way to keep good people around.” Good people like Hadley Kreitz, who arrived in Toluma in 2014 as an apprentice and worked her way up to herd manager, then cheese-maker, then added organic cultured butter to the creamery’s repertoire. When she married David Kreitz, a food-loving industrial designer who builds wood-fired ovens, a dream was born.

The new business gives her staff more opportunities, while allowing the farm to further diversify its market—which has kept them going through the current crisis. “Had we depended on just one buyer,” says Hicks, “or had we just been selling to restaurants, things would be a lot worse.” Instead, while some sales outlets have declined and their agritourism program is on hold, e-commerce sales have increased and their new business in San Francisco is focusing on takeout.

“With all these disruptions, I just hope we come out of this crisis with a deeper realization that where our food comes from matters,” Hicks says. “And we’re gonna need to address the bigger issues facing agriculture together.”

Near the town of Graton, for Lisa Gottreich, it’s the animals that drew her in: “My kids would say I love my goats more than them.” Thirteen years ago, she started Bohemian Creamery, milking 90 goats and making a variety of cheeses inspired by her years living in Europe.

On what she calls her “teat to table” days, Gottreich rises early to milk the animals, then heads into the creamery to make cheese. In the afternoon, she drives into San Francisco to deliver orders, stopping in at some of the finest restaurants, all founded on an appreciation for artisans like her. Chefs sometimes even “roll out the red carpet,” inviting her to stick around for a meal.

But those are the good days. It’s not always so glamorous, especially lately. COVID-19 has cut her sales by 70 percent and one employee left for health concerns. “It takes endurance,” she says, a warning to any starry-eyed, would-be farmers or cheese-makers. “The kind of endurance that’s hard to find. Any romantic bubble you might have will quickly burst if you’re afraid to work and work hard.”

Besides endurance, for Sonoma County it would seem that a niche product is the key to survival, be it goat milk, organics or unique cheeses. But while that niche market has allowed Gottreich and her peers to get by, she and many others recognize that such a strategy doesn’t solve the bigger issues like rampant consolidation in the industry, plummeting milk prices nationwide, or a trend that Lisa can’t help but notice:

“When I was a kid, there was one grocery store, and the mechanic and the doctor both shopped there. Now, food quality has become yet another benchmark in class differentiation. There’s Food 4 Less and then there’s Whole Foods. You’ll never see those two shoppers in the same place. As for folks like me, I can only afford to sell my products to one of those markets. That bothers me. Everyone deserves good food.”

411