A new book on the Fibershed movement acts as a toolkit for building a soil-to-skin approach to clothing in a fast fashion world.

When Rebecca Burgess started Fibershed a decade ago, the majority of Americans weren’t thinking too hard about the environmental and social costs of their clothing—especially “fast fashion.” Most still don’t.

“It’s become more of an emergency situation,” says Burgess, by phone. “The consumption rates are going up, the production of problematic blends—plastic blended into everything—has gone up. The situation has gotten worse in 10 years. The lion’s share of plastic in the [San Francisco] Bay is microplastic, and half of that is actually textile microfibers.” (Yes, those plastic-polluting textiles include your leggings.)

Fibershed describes a climate beneficial, regionally based textile system. Like a watershed or foodshed, the word signifies geographical unity and common purpose—an approach that localizes the production of clothing in a way that regenerates soil and land. It’s worlds away from the global, industrial, polluting model: 98 percent of America’s clothes are made in other countries, where waterways run gray with industrial chemicals from clothing factories, and the people who make the clothes are working in toxic, hazardous conditions for low wages.

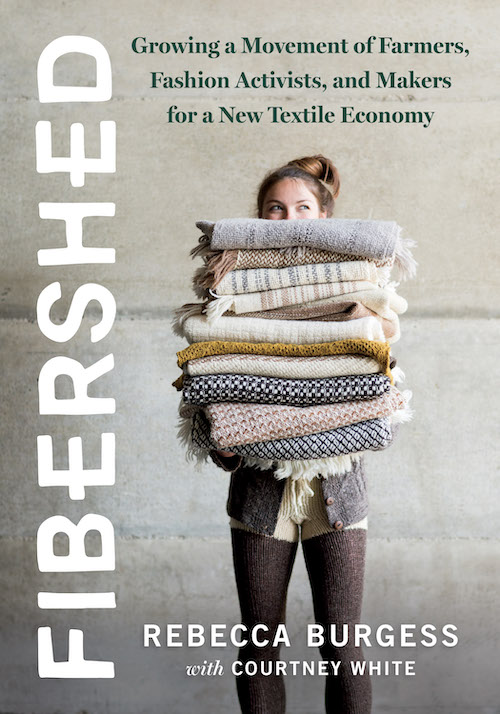

Burgess’s new book, Fibershed: Growing a Movement of Farmers, Fashion Activists, and Makers for a New Textile Economy (Chelsea Green, 2019)—a textbook, manifesto, and toolkit for the whys and hows of building a Fibershed community and infrastructure—aims to change that.

“Similar to a local watershed or woodshed, a fibershed is focused on the source of the raw material, the transparency with which it is converted into clothing, and the connectivity among all parts, from soil to skin and back to soil,” writes Burgess in the introduction. It’s obvious from the photos, makers, and farmers spotlighted in the book that Sonoma County is a core Fibershed region.

“Sonoma County has the most Fibershed producers per capita,” says Burgess. “There’s wool in spades. There are a lot of people with vineyards grazing sheep. There are a lot of people raising alpacas and Angora goats. Just really unique projects. I think it’s the way it’s zoned. You have these postage-stamp lots, where people do their hobby farms.”

The Fibershed story started when Burgess, a trained weaver and natural dyer, began to think seriously about the environmental impact of her own clothing. She’d been deeply influenced by time living in Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia, where she witnessed first hand the impacts of synthetic dye manufacturing on the land and people. On returning to the Bay Area, Burgess committed to a personal experiment. Would it be possible to source a functional, bioregional wardrobe from within no more than 150 miles of her home in San Geronimo? She collaborated with fiber producers, organic farmers, knitters, and designers to create a year-round wardrobe. With virtually no mills or other infrastructure in place, it wasn’t easy, but she was able to pull together something workable.

Once the experiment ended, and not willing to let go of the groundwork that had been established, Burgess developed Fibershed into a nonprofit in 2012.

“The idea was floated to start a nonprofit organization to uphold a mission focused on local fiber and natural dye systems,” writes Burgess. “We saw the positive role that local food systems’ organizers had in helping community access locally grown, healthy foods, but there was nothing analogous in the fiber-and-dye system to support access to locally produced, clean, healthy textiles.”

The nonprofit’s goals are ambitious: to develop regional- and climate-benefiting fiber systems on behalf of independent working producers, to implement carbon farming, to rebuild regional manufacturing, and to connect people with farms and ranches through education.

Despite the growth in micro-plastic production and other signs that the message still needs to get out there, Burgess has seen much progress. The nonprofit has raised millions of dollars in capital. They’ve started rebuilding the textile industry locally by applying the capital to the development of two small mills. But that work has only just begun to decentralize and re-localize textile manufacturing.

“You can’t rebuild an industry without rebuilding the system,” says Burgess. “When you break a system, like we did after NAFTA and CAFTA, then it doesn’t happen with a snap of your finger. You lose skill sets like breeding practices, agricultural production goes to other crops, people leave the state because blue-collar work is no longer supported in California. People don’t understand how delicate, inter-related, complex and dynamic any of these systems are that create clothing.”

On Nov. 14, 2020, Fibershed hosts a Wool Symposium in Point Reyes Station. Open to the public and tickets available on the fibershed website.