The ‘OAEC Cookbook’ encourages us to eat widely and well.

There are perhaps some things that the Occidental Arts and Ecology Center (OAEC) folks can do that you can’t. Live peacefully in a commune for 21 years, for example. Own 80 acres in a pristine West County landscape. Form a nonprofit with the members of your intentional community and don’t screw it up. Work from home teaching thousands of people how to do what you do. Maintain, enlarge, and propagate a “mother garden” that contains a wild amount of biodiversity and offers a continuous food production cycle amid more wind, rain, fog, sun, and hail than the postal worker of yore ever had to slump beneath.

But there are a few things that they do that mere mortals might attain. Grow a garden. Buy what you can’t grow from those who can. Eat meat. Cook at home. Remember to smile now and then.

But there are a few things that they do that mere mortals might attain. Grow a garden. Buy what you can’t grow from those who can. Eat meat. Cook at home. Remember to smile now and then.

Indeed, even those of us puttering about without a large band of eager young interns ready to assist can coax a head of lettuce fairly regularly from the soil, can remember to pick the borage flowers that pop up of their own volition, and can learn to look, really look, at the ground they inhabit.

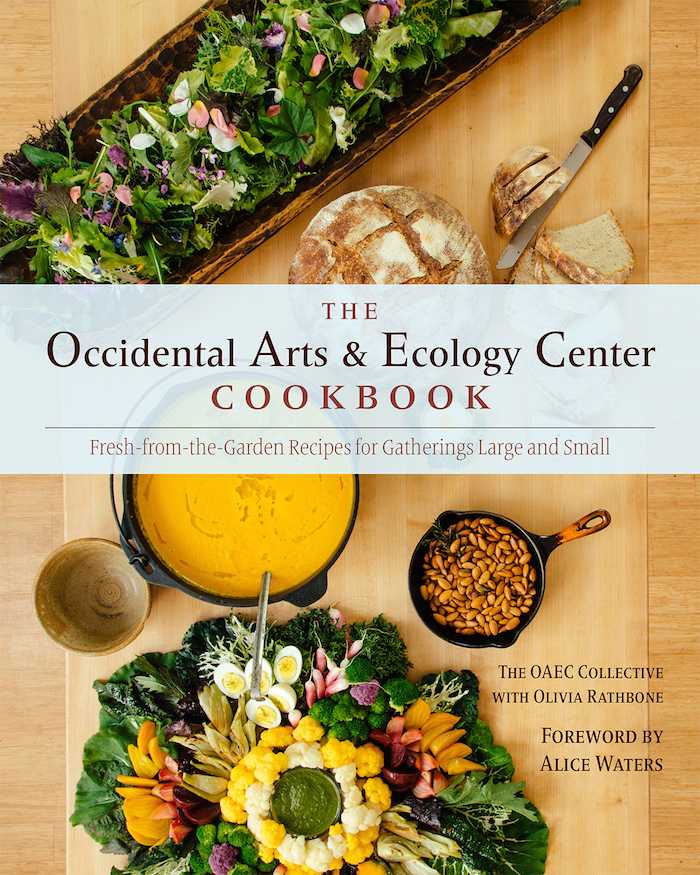

These and other simple lessons are among the pleasures of the OAEC’s eponymous new Cookbook (Chelsea Green; $40), a richly illustrated photo-heavy 416-page declaration of intent, process, and good ways to eat from the land, whatever your land might be.

Founded by seven friends in 1994 as the Sowing Circle intentional community and soon incorporated as a 501(c)3, the OAEC exemplifies the human interdependence that their innovative permaculture design work encourages in the plants and trees that surround them.

But no one expects you to live like this. What they do wish to expect is that you try new things, consider the natural world, plant a few vegetables in whatever space you might have or buy them from those who have the space, and prepare your meals at home more often than not. To that end, their cookbook offers recipes on a vast swathe of foodstuffs that we as OAEC neighbors can likely grow or purchase ourselves.

Because the OAEC has such a robust seasonal visiting schedule, the recipes here are cleverly calibrated for either four to six people or 30 to 40 hungry folks. They’re used to feeding a crowd, and an enduring and crowd-pleasing dish that visitors have come to expect is one of their epic salads.

Called the “biodiversity salad mix,” this collection of propagated and foraged foods changes with the seasons, as the cookbook deftly illustrates. Mother Garden biodiversity director Doug Gosling, in charge of the collective’s nightly salad, has such a wealth of options available that he sometimes picks solely for color palette. In spring, it might contain tulip petals and broccoli leaves amid the myriad; in the summer, rose petals and celery flowers. While his salads always feature a lettuce or green of some type, the point being celebrated is that “salad” isn’t solely Romaine or Iceberg glopped up with something from a bottle but rather, a living expression of what’s happening on the earth the very day you sit down to eat it—and that said eating should be fearless in its wandering and appetite for taste.

With a temperamental old stove, cooking pots meant to produce food for 40, and the odd hand deciding what a “dash” or a “splash” might mean, the OAEC offers a recipe collection meant for a home cook used to the vagaries of cooking. A seasoned cast iron skillet heats up differently than does a sleek new Cephalon pan and the difference will show. Rather, these recipes are intended as a guide, and the text as a history and a primer of what one group of people decided to do with their lives and their senses.

As pleasurable to simply read as it is to cook from, the OAEC Cookbook, primarily written by Olivia Rathbone but naturally contributed to by all members of the community, offers such wisdom as that chamomile will get bitter if boiled (and make you sleepy!), how best to cook cactus, that seed saving is a radical act, how to start your own sourdough, the role of rosemary in transforming whipped cream, that carnations taste of cloves, why lemon verbena is good with steamed rice, and how sometimes in the winter you are simply so very glad that all visitors have gone home and you’ve got the whole damned 80 acres to yourselves.

Article Resources:

oaec.org/our-work/projects-and-partnerships/cookbook

Recipe

Making Quick Fire-Roasted Vegetables

A simple tip from the OAEC ‘Cookbook’ Summer veggies such as peppers and eggplant can quickly be charred on a grill or gas stovetop for adding rich, fire-roasted flavor to any dish.

Place whole peppers or eggplant directly over an open flame, ideally on a grill above a blazing wood fire—this is a nice task to take advantage of the high flames licking up at the beginning stages of getting a bed of wood coals going for a barbecue. You can also place the vegetables directly on the gas burner of the stovetop.

Place whole peppers or eggplant directly over an open flame, ideally on a grill above a blazing wood fire—this is a nice task to take advantage of the high flames licking up at the beginning stages of getting a bed of wood coals going for a barbecue. You can also place the vegetables directly on the gas burner of the stovetop.

Take care and attend to them constantly, turning them with tongs to get an even char on the outside skin. When they are good and black all over, place them in a stockpot with a tight-fitting lid so that they continue to cook and sweat in the heat generated from charring.

After 30 minutes or more in the enclosed pot, they should be cool and ready to be processed. Rub the skin off with your hands or with a towel to expose the flesh; discard charred skin and seeds. Slice into strips or use as directed in your recipes. Save the juice that remains in the bottom of the pot—you may want it for your recipe or for livening up a soup or salad dressing.