Is Dry Farming Making a Comeback

Rewards taste sweeter when you have to work for them. And for thousands of years, deep underground, that’s how vines have brought us grapes. From the prehistoric Levant to the Spanish missionaries who bottled Sonoma these plants can thrive without a single drop of irrigation. As Tony Coturri explains, during the first two years after a vine goes in, they employ a mobile watering system wheeled between the rows to help the plants get established– enough to sustain the young plants, but not so much that Valley’s first vintage, vineyards have thrived in dry climates where their roots search deep into the earth for moisture and nutrients. And it’s the very strain of that subterranean struggle that, above ground, results in rich sugars that yeast will feast upon to produce what Plato once swore was the gods’ greatest gift to humankind.

Rewards taste sweeter when you have to work for them. And for thousands of years, deep underground, that’s how vines have brought us grapes. From the prehistoric Levant to the Spanish missionaries who bottled Sonoma these plants can thrive without a single drop of irrigation. As Tony Coturri explains, during the first two years after a vine goes in, they employ a mobile watering system wheeled between the rows to help the plants get established– enough to sustain the young plants, but not so much that Valley’s first vintage, vineyards have thrived in dry climates where their roots search deep into the earth for moisture and nutrients. And it’s the very strain of that subterranean struggle that, above ground, results in rich sugars that yeast will feast upon to produce what Plato once swore was the gods’ greatest gift to humankind.

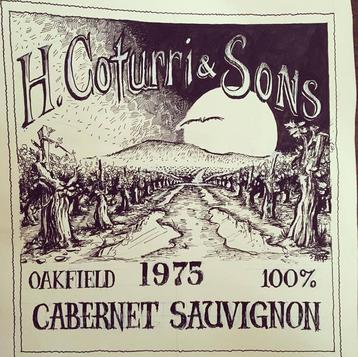

Such a gift was wine that despite America’s prohibition in the 1920s, an Italian immigrant named Enrico Coturri began bootlegging in San Francisco, passing on his Old World winemaking traditions to his son, Harry, and grandsons, Tony and Phil, who in 1979 founded Coturri Winery near Glen Ellen. There, as in much of Italy, the lopsided Mediterranean climate brings winter rain and a long growing season when scarcely a drop falls from the sky.

Crops like lettuce or corn grow shallow roots, requiring either sufficient rainfall or ample irrigation. Soil quality may contribute to a vegetable’s taste, but with only a few inches of earth for their roots to explore, it’s no wonder that we never hear about the terroir of romaine. The roots of a single vine grown at Coturri, on the other hand, will tap into a vast swathe of the land beneath them, picking up the unique character imbued by nature.

But beyond terroir, another advantage of the grape and its adventurous roots: despite California’s long dry season, they bunch at the surface waiting for more. The vines are trained to reach down in search of whatever moisture winter left behind. Today, Tony is pulling nearly four tons of fruit per acre from vines that haven’t been irrigated for decades.

But beyond terroir, another advantage of the grape and its adventurous roots: despite California’s long dry season, they bunch at the surface waiting for more. The vines are trained to reach down in search of whatever moisture winter left behind. Today, Tony is pulling nearly four tons of fruit per acre from vines that haven’t been irrigated for decades.

Coturri practices what is known today as “dry farming.” But, as he explains, when they started back in the 1970s, they just called it farming. Most vineyards were dry-farmed then, and many regions elsewhere in the world remain that way today—in fact, some European appellations legally forbid irrigation. But here, what’s unique about Coturri is that they’ve held to their traditions while the California grape industry transformed around them.

WATER MATTERS

New dams, river diversions, advances in well-drilling, and the advent of drip irrigation led to a massive shift in American grape farming, and agriculture more generally, from a delicate dance with nature’s cycles to an industry in pursuit of better control, predictability, and higher yields. These changes allowed viticulture to expand into regions previously unworkable, from remote corners of the North Bay wine country to the arid deserts of the Central Valley.

New dams, river diversions, advances in well-drilling, and the advent of drip irrigation led to a massive shift in American grape farming, and agriculture more generally, from a delicate dance with nature’s cycles to an industry in pursuit of better control, predictability, and higher yields. These changes allowed viticulture to expand into regions previously unworkable, from remote corners of the North Bay wine country to the arid deserts of the Central Valley.

A 2020 study from UC Davis estimated that in Napa, Sonoma and Mendocino counties, an average vineyard irrigates 5.72 acre inches annually. With 121,763 acres of grapes in this tri-county region, in all, nearly 19 billion gallons of water or 1/3 of the capacity of Lake Sonoma gets dripped onto a crop that, a couple generations ago, used almost none.

It wasn’t just irrigation that changed. With Sonoma County’s grape industry transforming into a $11 billion industry, new players arrived to the game. “When we got started,” says Tony, “the guy out on the tractor was usually the guy who owned the land. Nowadays, the guy out on the tractor doesn’t even know who owns the land.” Enter the investors, the labor contractors, the tourism industry, and of course, the rise of vineyard management companies.

It was into this new-fangled world that John Mason got his start. Retired from firefighting, John purchased a few acres near the Russian River where, according to him, he started backwards: planted a vineyard first, learned about viticulture second. Along with classes at Santa Rosa Junior College, John took a summer job with a vineyard consulting firm. Learning to use sophisticated tools that measure soil and plant moisture, he traveled across the North Bay monitoring vineyards and providing detailed data that growers could use for more efficient resource management. Most of these vineyards, he soon learned, were using way more irrigation than necessary. But too often, even after his data recommended a reduction of water, the irrigation was back on a few days later—in some cases as much as eight hours weekly from June onward.

This experience, coupled with learning about more natural approaches to viticulture, compelled John to begin weaning his own vines off irrigation. After just a couple of years, the quality of his grapes vastly improved. Chef Alice Waters thought so, as she brought bottles from John’s Emtu winery to President Obama’s inaugural event and served them at her esteemed Berkeley restaurant, Chez Panisse.

TOUGH TO PREDICT

So if dry-farming improves wine quality while using less of a scarce resource, why has the industry so uniformly shifted to irrigation and, as some argue, over-irrigation?

So if dry-farming improves wine quality while using less of a scarce resource, why has the industry so uniformly shifted to irrigation and, as some argue, over-irrigation?

In an industry where bottles can range from $2 to $2,000, some growers focus on quality and others on quantity. Irrigation can increase a vineyard’s yield. Squeezed by California’s skyrocketing land costs, growers will fit as many vines per acre as possible, a density too crowded for expansive dry-farmed roots. Some simply prioritize pumping grapes full of water. Irrigation opens up shallow soil to grape-growing, only requiring those top few inches for root growth. New rootstock varieties can sacrifice a dry season tenacity for earlier fruit set, greater yield or disease resistance.

But of all the reasons for irrigation’s modern ubiquity, the greatest, according to John, Tony and other dry-farmers, is a sense of control. Farming has always been a gamble, but nowadays, not only are the costs of doing business higher, but climate change has made volatility the norm. Unprecedented heat waves, droughts, and flash flooding has, for some, made farming with nature more of a wrestling match than a dance.

“Folks don’t want to take chances,” says Daniel Schoenfeld of Wild Hog Winery in Cazadero. “The financial loss scares people. It’s the same reason they spray like crazy. Because they had mildew 25 years ago.” When Daniel got started in 1981, he thought he could recognize the annual patterns, but today, “I’ve given up thinking I know them. There is no such thing as an average year anymore.”

During the 2020/21 season, Will Bucklin of Old Hill Ranch near Sonoma saw only 14 inches of rainfall, “But at least it didn’t come all at once like it did this year,” he says, “when water just rushed off the land. With that kind of variation, it’s tough to predict an annual cycle.”

Even here, at one of Sonoma’s most historic vineyards, dry-farmed since 1851, Will is unsure what the future holds, given that dry-farming viability typically requires 20 inches of rain minimum— which is why he’s kept close tabs on Australia, where 20 years ago a mega-drought devastated the south of that country for an entire decade. While during California’s shorter droughts, explains Will, dry-farmed vines performed better than those irrigated. But in Australia, a full 10 years of empty skies left even the deepest roots parched, and the only vines that survived were those sustained with irrigation.

Even here, at one of Sonoma’s most historic vineyards, dry-farmed since 1851, Will is unsure what the future holds, given that dry-farming viability typically requires 20 inches of rain minimum— which is why he’s kept close tabs on Australia, where 20 years ago a mega-drought devastated the south of that country for an entire decade. While during California’s shorter droughts, explains Will, dry-farmed vines performed better than those irrigated. But in Australia, a full 10 years of empty skies left even the deepest roots parched, and the only vines that survived were those sustained with irrigation.

If not from the clouds, water has to come from somewhere. In California, that means ever-depleting surface water from streams, rivers and reservoirs or pumped up from aquifers. It may be too late for places like the Central Valley where the ground is literally subsiding, irreparably diminishing the aquifers, in large part to export water across the globe in the form of almonds, pistachios, and grapes.

So how do we balance the risks of farming with the dire need to protect our precious water?

Back at Old Hill, Will recounts a few acres of cabernet they planted on a new block that turned out to have shallow soil due to the abnormal geology below. The vines struggled to produce. He finally caved, installing irrigation. But because he’d used the same old dry-farming techniques from the get-go—from root stock selection, to plant establishment, to spacing—he was able to use far less water. And when drought hit, those better adapted vines, with less water, outperformed his neighbors’.

Back at Old Hill, Will recounts a few acres of cabernet they planted on a new block that turned out to have shallow soil due to the abnormal geology below. The vines struggled to produce. He finally caved, installing irrigation. But because he’d used the same old dry-farming techniques from the get-go—from root stock selection, to plant establishment, to spacing—he was able to use far less water. And when drought hit, those better adapted vines, with less water, outperformed his neighbors’.

“Dry farming is a verb, not a noun,” says Frank Leeds of Frog’s Leap Winery who dry-farms just over the hill in Napa. “It’s not about what you can’t do, but about what you do to assure those vines thrive.”

The future of California’s water is at a crossroads, as is its agriculture. But at least among the North Coast’s vineyards, we have the potential to continue producing some of the best wines in the world with less than 19 billion gallons of water. Honoring the resilience of the grape might just mean letting those roots roam free.

Photos courtesy of Will Bucklin, Emtu Estate Wines, and Coturri Wines