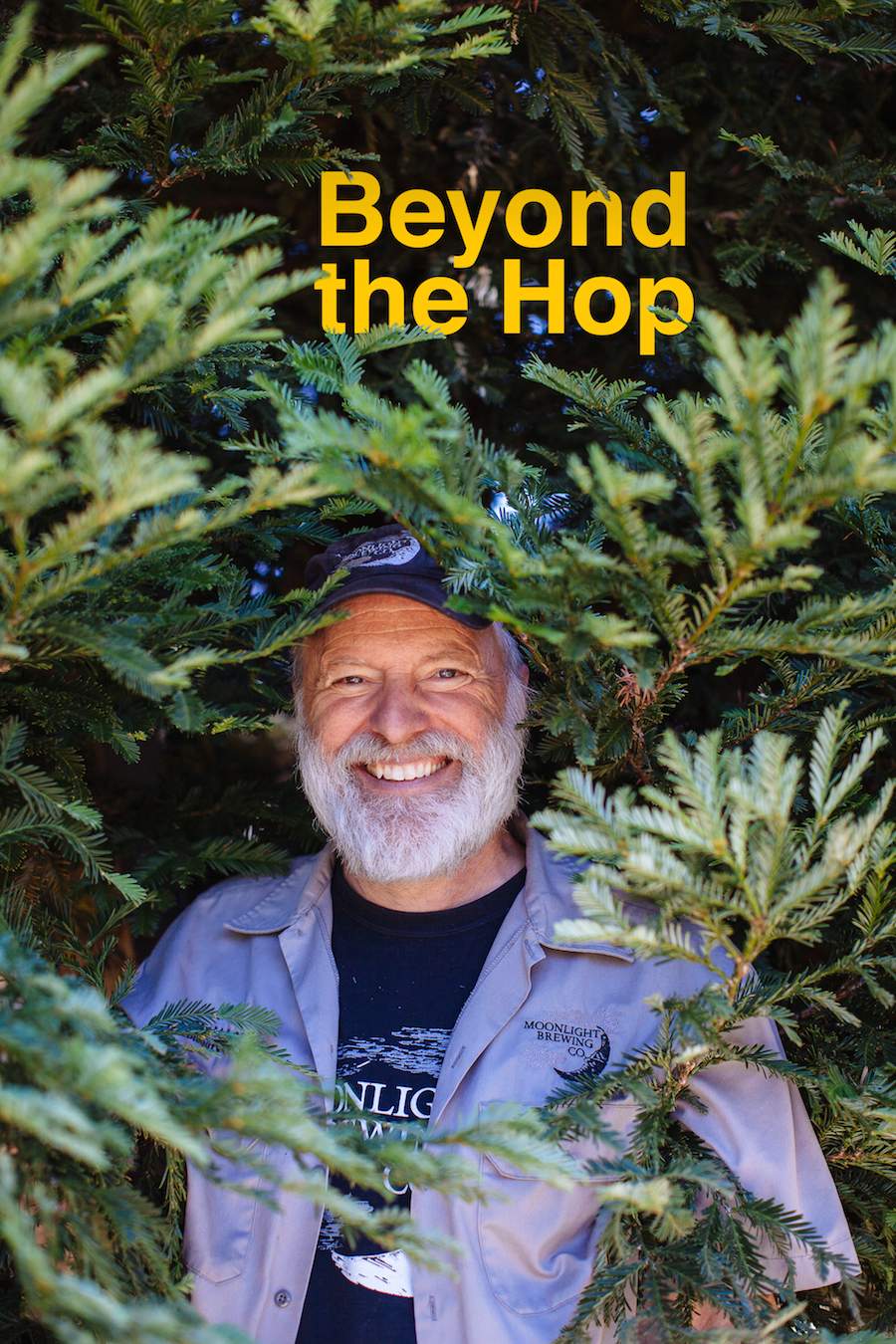

Brian Hunt and the thirst for something different.

Grain-based beer has been brewed for thousands of years, while hops have been in use only for several centuries.

So, for brewer Brian Hunt, our culture’s fixation on the aromatic European flower Humulus lupulus ranges from amusing to annoying. The owner and operator of Moonlight Brewing Company, Hunt works out of his home in the woods west of Santa Rosa. He brews and distributes in kegs to bars and restaurants throughout the Bay Area. He likes hops—and even grows them—making many beers heavily fragranced by the uniquely aromatic blossom. But Moonlight beers are well known for their unconventional nuances, and some of Hunt’s most sought-after beers are made with virtually no hops at all.

Hunt reaches into the landscape around him to make his beers, using things like wild herbs and conifer tips. But he insists he is not being innovative, or extreme, or even particularly creative. Rather, Hunt is reviving traditions of brewing that were long ago abandoned as the use of hops became standardized and, to some degree, required.

Indeed, to legally label and sell his products as beer, Hunt must add hops. Most of his beer contains a relatively standard dosage, in fact. That’s because that is what the market wants, says Hunt, whose signature beers include a “Twist of Fate” amber ale, a “Bombay by Boat” IPA, and a “Reality Czech” pilsner.

But for his fun stuff, he trims the hop additions down to the legal minimum required by tax laws. Then, he does what most other brewers don’t: He adds weird things. He spices his “Working for Tips” beer with the soft, green springtime shoots of redwood trees that grow on his property. His “UncleØlsen” is made with incense cedar. Other limited edition beers contain yarrow, mugwort, Labrador tea, bay leaves, and bee balm. He also uses “regular grocery store items” like tomatoes, basil, peppercorns, and apricots to flavor his beer. He buys some ingredients from local farmers; others, from the Sonoma County Herb Exchange.

Hunt has labored through written histories of beer. He received a bachelor’s degree in brewing from UC Davis in 1980. He has amassed a mental encyclopedia of beer’s history—and what fascinates Hunt as much as anything else in brewing is the fact that the standardization of hops as a brewing essential is rather arbitrary. He says many other plants have the capacity to do what hops do—provide the balance of flavor that most beer needs to appeal to the human palate.

Specifically, Hunt explains, unspiced beer is too sweet, as a significant fraction of the sugars in a brewing base don’t ferment, leaving what brewers and winemakers call “residual sweetness.” This potentially cloying element can be offset with bitterness or astringency—and hops have the fantastic capacity to achieve this goal while providing beautiful aromas that cover much of the tropical fruit spectrum. The acids in the flowers also help preserve the beer.

But beer originated long before the advent of refrigeration technology, when brews stored at barn or cave temperature gained longevity from hops and even depended on them. Today, hops aren’t needed as a preservative. Rather, they do little more than meet consumers’ expectations of flavor and aroma—and in Sonoma County as much as anywhere, that expectation drives an industry. Heavily hopped beers are tremendously popular. Many brewers put as much hop oil extract into their beers that they reasonably can, and they name them things like “Tricerahops,” “Hop Stoopid,” “Hoptologist” and other clever catch phrases and puns. Festivals showcasing these IPAs, double IPAs, and triple IPAs are held nationwide, and in Hunt’s backyard, at Russian River Brewing Company, an annual circus occurs attracting throngs of people who call themselves “hopheads,” all clamoring to have a taste of one of the most coveted bitter beers around, a limited release Triple IPA called “Pliny the Younger.”

For people who think that beer should have a hoppy taste, unhopped beers may seem scary or immoral. Brian Hunt

Hunt says he enjoys a bitterly hopped IPA now and then. But mostly, he wants balance, and he believes many mature beer drinkers do, too, whether they realize it or not.

“For people who think that beer should have a hoppy taste, unhopped beers may seem scary or immoral,” Hunt says. “But sometimes I’m able to find people who say, ‘Oh, I only like hoppy beers,’ and I’ll give them something unhopped that they actually adore. Often when people say they only like beers that taste hoppy, I find that what they mean is that they like beers that have significant flavor and character.”

Hunt, surrounded by redwoods and a forest of other opportunities, expects the madness over that singular little flower with the uncanny aroma will eventually generate a reaction trend—a backpedaling movement away from hops. Indeed, he says it’s already happening as drinkers begin to reject highly hopped beers and the pendulum swings toward beers that are flavored with other plants. In a way, then, the American hop craze is actually giving Hunt an opportunity to carve out his niche. “These incredibly hoppy beers are pushing the demand for an alternative reaction, and ironically, that is happening in exactly the same way that the blandness of the macrobeers pushed people in the opposite direction toward really hoppy beers,” he says.

Through his decades of brewing, Hunt has watched the brewing industry explode. In 1980, when he graduated from UC Davis—and just a few years before he moved to Sonoma County—Hunt says there were about 40 brewing companies in the United States. That’s about as many breweries as are in the North Bay today.

But, in spite of the wealth of beer brands and styles available, and with the brewing industry at large yet to branch out beyond the hop, beer itself, as a craft product, remains in a state of infancy. Hunt is waiting to see how it grows.

“There has been an incredible renaissance in beer diversity, but what I find hilarious is that we haven’t yet scratched the surface of where we can go,” he says.