Wine and beer make room for a new boom in spirit distillation.

You could be smelling one of any number of things,” Adam Spiegel says matter-of-factly as we quite literally sniff about the 750 square feet that currently comprises the heart of his 1512 Spirits distillery in Rohnert Park. Rye grain, steam, malt—who knows what’s in the air at this particular moment.

Sonoma County residents are used to our agricultural odors, whether they be the tang of cows and pigs and sheep, the sweet rot of harvest, or the sharp scent of beer on the boil. Increasingly added to our olfactory slate is the smell of grain toasted and mashed to make local whiskey, gin, vodka, and rye.

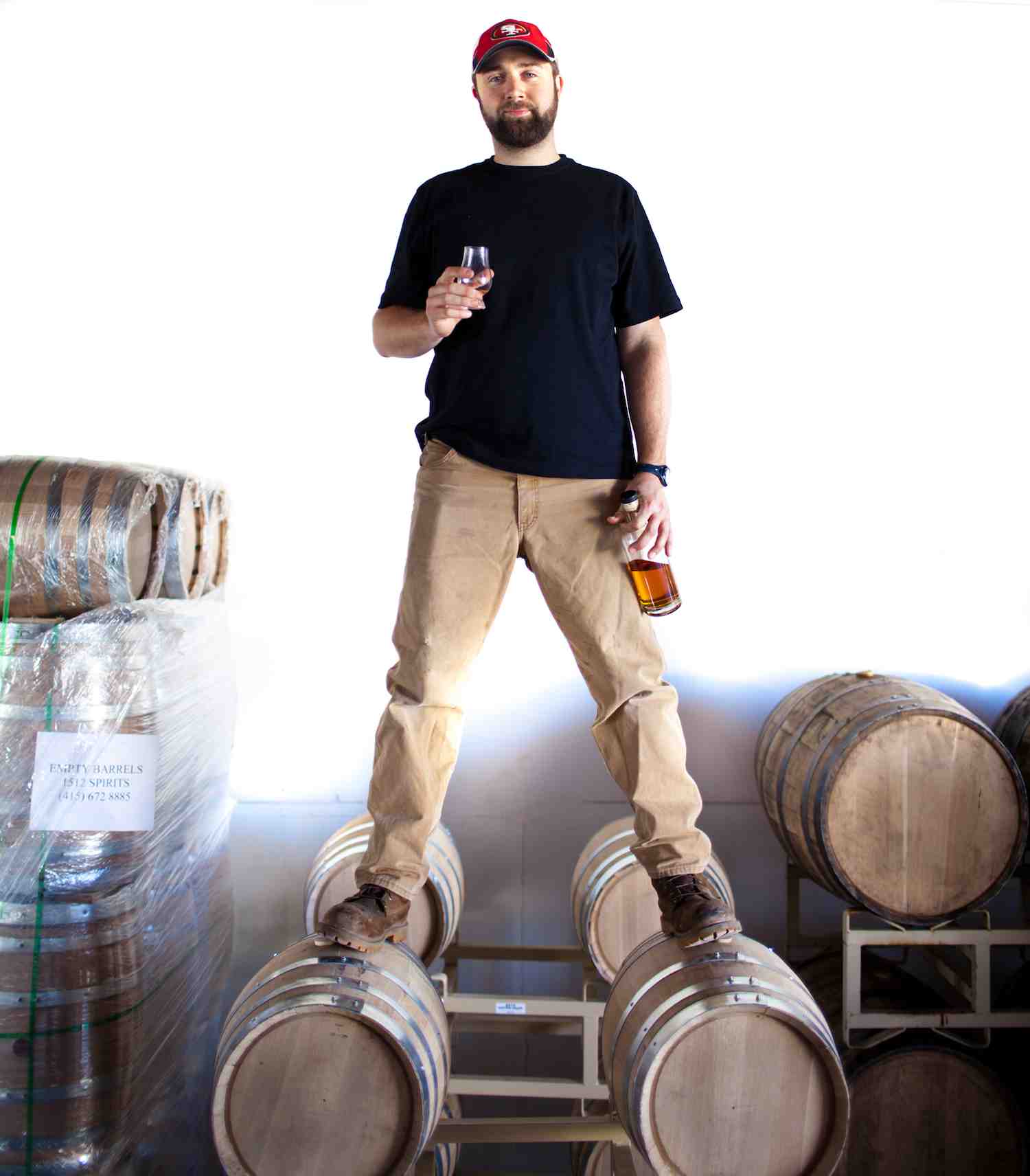

Spiegel, 29, is among a new group of entrepreneurs who find satisfaction not in the mug or the flute but by the ounce.

1512 Spirits (soon to be renamed Sonoma County Spirits) joins the Still Water Distillery in Petaluma, Spirit Works in Sebastopol, and Lemoncello in Sonoma—among others—that are based here in Northern California’s wine country but making something distinctly more robust.

Spiegel’s journey began in 2008 with a hair cut, the old-fashioned kind that includes a hot shave with a straight razor, at the 1512 Barbershop in San Francisco. Once in the chair with proprietor Sal Cimino, the two men got to talking.

“We built a friendship,” Spiegel says, “and, over time, we started talking about his passion, which is making spirits. I learned very quickly that his grandfather had taught him how to make certain things—and he was making grappa on Potrero Hill. I was born and raised in San Francisco, and I just fell in love with the idea and the nostalgia of it all.”

The two men soon went into business together, making rye whiskey. “I was looking to actually produce a product,” Spiegel says. “I thought that to do something with your hands that you can control from start to finish is an amazing thing. Nowadays, you don’t see a lot of people who are doing that.”

By 2010, Spiegel was working full time in their small Rohnert Park space to build the company; Cimino worked part-time while maintaining his barbershop. Eventually, the strain became too much and Spiegel bought Cimino out.

Spiegel is a serial entrepreneur who ran a successful business catering to college students while he himself was in college. He started another one just out of school that didn’t do so well.

“The thing is, every time you try things, you learn,” he says. “A lot. And now I’ve gotten to a point where I can wake up in the morning and actually love what I do. I worked in financial sales before I got into working at this full-time. I think that the financial crisis really taught me something, which is that there is more to life than going to work and doing something you hate just for the check. Why do that? Now I wake up every single morning renewed and excited about the day.”

Good thing, because this is a seven-day-a-week gig. Spiegel and his two employees are expanding their distillery to a larger space they’re rehabbing around the corner from their current spot, a production facility with one room for the mash, another for the distilling, and hopes for a tasting room now that California state law allows distillers to charge for tastings.

“This was always a dream that Sal and I had a long time ago, to be able to reduce mashes in a separate facility than you distill in,” Spiegel says. “When you’re tripping over that many cords and pumps, it’s not safe. Also, you want to be able to do separate processes in separate spaces. It’s like to each man or woman their own trade.”

Spiegel sources his rye grain from Canada, where it is plentiful, using about 3,000 pounds a month to create around 400 gallons of rye. He uses old-fashioned alembic copper stills, the kind brought to Europe by the Moors in the 1100s to purify their water. European monks took one look at those stills and wisely thought, cognac. He and Cimino built the fire boxes that the stills sit atop; Spiegel and his father-in-law-to-be built the barrel shelves. This is a handmade business, but there’s no doubt that it’s a going operation.

My goal is not to modify it once I have my pure spirit. This is nature. I'm not trying to speed up the process. Adam Spiegel

Priced at around $60 a bottle, 1512 Spirits can be seen as pricey, but perhaps not so much when you consider what goes into making each bottle.

“I’m kind of a purist,” Spiegel says. “I try not to draw flavors other than malted rye, unmalted rye, yeast, and water. Those are my flavors. When I put it in wood, it’s new-char American oak. That’s it. My goal is not to modify it once I have my pure spirit. This is nature. I’m not trying to speed up the process.”

Timo and Ashby Marshall of Spirit Works Distillery, open in the new Sebastopol Barlow complex, are in no hurry, either. The Marshalls met working as sailors and deckhands on boats and settled in San Francisco for access to the ports. But day-tripping to West County changed everything.

“We fell in love with the place and wanted to retire here, to grow old,”

Timo says. “We started looking for a way to make that happen.”

Timo’s family had made sloe gin for generations in England and the couple thought to produce the botanicals for the stuff here and sell it to distilleries. Then they discovered that almost no one in the U.S. makes their gin pure, from scratch.

“Most will buy alcohol and manipulate it into another form,” Timo says. “The more we started looking into it, the more we realized that the distilling side was something that really excited us. The idea of growing the botanicals became less appealing and, once we committed fully to the distillation, it was obvious that we should see what we could achieve with it.”

What they’ve achieved is a large, gleaming facility with four full-time employees who produce a wheat-based gin that can be used as a vodka early in the process and made sloe with additional ingredients. They source their wheat from a farm near Sacramento because they had so much trouble finding non-GMO corn, a more traditional base grain.

“We have a list of requirements that our raw materials fall under,” he says. “The most important ingredient is the quality of the raw product.”

The Marshalls add coriander, cardamom, angelica, and hibiscus to their tank, hand-zesting lemon and orange into the brew on the days they distill. And because they’ve got the large, gleaming place, they need to keep it busy.

“There are times when the still isn’t running and we have to make as much use of our still as we can,” Timo says. “We can make a rye whiskey and very traditional West Coast-style whiskey and a brandy. There’s a slight diversification, but our focus is and will remain gin.”

The sudden boom in microdistilleries doesn’t seem to phase the folks who created the boom.

“My goal as a small business owner is to make a product that I can stand behind that I made with the help of my incredible employees,” Spiegel says. “It’s through that partnership that we grow. I’m not worried about competition. I welcome them, because frankly, the more of us there are, the better.

“Having more distilleries in the local area allows us to elevate the conversation.”