Healdsburg Artist Throws a Pot on Mt. Everest for Arts Scoloarship

Ain’t No Mountain High Enough.

When Robert Weiss attended a high school graduation in 2003, he was gratified to learn that the graduating class had racked up 122 scholarships among them to help offset college costs. But he was also horrified. Only one of those scholarships was for an education in the fine arts.

Weiss, 69, trained at the prestigious Otis School of Design for his undergraduate work and that background has served him well. A professional ceramicist and serial entrepreneur, Weiss has done everything from own a restaurant to run highly successful pet and fish food companies. Regardless of what he has endeavored to accomplish in his day job, he has always come back to his wheel.

Invigorated by the gap he perceived in support for arts education, Weiss began giving away his own money in scholarship, making it a personal rule that every cent he earned from his ceramic and photography interests would go to funding art school scholarships. Of the 63 scholarships he’s funded over the last 13 years, some have consisted of thousands of dollars; others, barely hundreds. It’s the vagary of the trade.

Forget about the Guinness Book of World Records (and this actually was a world’s record), setting his sights on Mt. Everest meant Weiss had to figure out how to throw a pot at roughly 17,000 feet altitude. It meant he had to figure out how to throw a pot—which requires fluid water as well as working fingers—in below freezing temperatures. And it ultimately meant that he had to figure out how to get the equipment to throw a high-altitude pot in freezing weather up a good portion of Mt. Everest to a base camp at 17,000 feet. Getting a portable wheel itself was the easy part.

Weiss set up an IndieGoGo campaign and spread the word among friends and supporters. He trained for the trip by throwing pots in a friend’s walk-in freezer, discovering that he could work for up to 12 minutes at a time before his hands froze, the bones feeling as if they would crumble inside his skin. What he hadn’t really considered was that, when he walked out of a Sonoma County freezer in early autumn, the mild 70-degree weather quickly warmed him up. But when he worked at the North Base Camp of Everest in November, with wind chill factors bringing temperatures down just a skosh past zero degrees Fahrenheit, the swift Tibetan winds would make him unable to warm up. Weiss credits his Sherpa’s quick thinking for saving him from frostbite.

But how can you know everything that will happen when you decide to do something that no one has ever yet attempted?

Planning the trip, Weiss considered and then rejected the purchase of a transformer to work with the electric cable that would run his potter’s wheel. Contracting with a tour company—which is the only way that foreigners can visit Everest’s North Camp, located as it is in Chinese controlled Tibet—he figured that he’d have what he needed with a gasoline run generator. Surely, the voltages would match up. They didn’t.

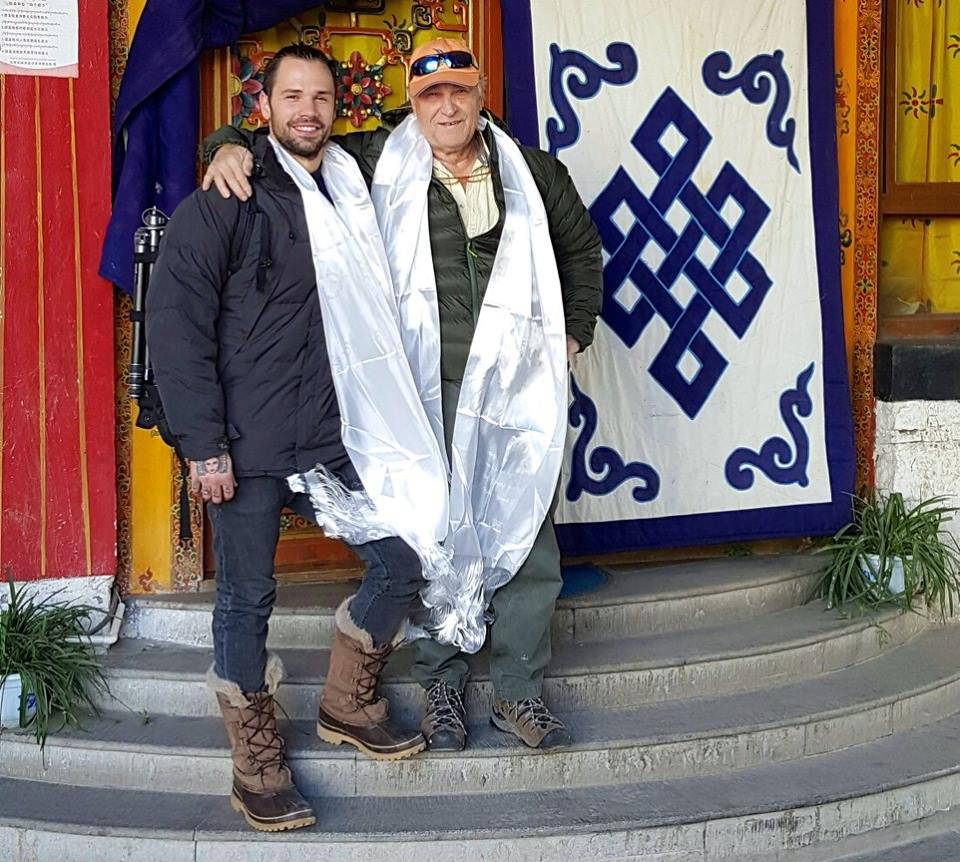

Weiss and his companion Kirk, the 30-something boyfriend of one of his three daughters, spent a mournful day wandering Lhasa looking fruitlessly for a transformer that would work. The two men had come so far to be thwarted by a detail so small. But lo, in a store that sold the kind of oversized chandeliers only ever found in hotel lobbies, they discovered perhaps the one transformer in all of Tibet that could work for them.

With the basics sorted, the duo and their guides began the trip up the north side of Everest. They stopped at 13,000 feet and Weiss threw his first pot, a test run for the one he would throw at base camp to raise scholarship funds. He was delirious, with a blood oxygen reading of just 78 percent (normal is in the high 90s), and afraid to go fully to sleep for fear he wouldn’t wake up again. He slept sitting up so that, when deep sleep overcame him, he’d topple over and wake up again. He did this for four nights, averaging two hours of sleep each evening. He began to hallucinate. Meanwhile, Kirk suffered cerebral edema, his brain stem swelling painfully into his skull, producing a high octane headache that never ceased. Weiss is only halfjoking when he says that he considers himself lucky to have a small brain.

Wearing three pairs of pants and four jackets, Weiss made it to base camp. Working quickly, he and his team set up the wheel, got out the clay, hooked everything up to the generator, and melted some water. Less than 12 minutes later, Weiss had a pot with four distinct ridges along the top representing each of the four peaks ringing Mt. Everest. Quickly, he packed it with the one he had made at 13,000 feet in a box he had rigged up from some cardboard days earlier, when he had the luxury of a hotel room in which to work.

As Weiss packed up, Kirk wandered off, interested in the scenery. But there is no “wandering” on Everest without a permit, and even his short foray legally constituted the start of a climb. An unpermitted climb. A military vehicle came slowly up the road. With the generator, electrical lines, and potter’s wheel stowed inside the car where the Chinese military couldn’t see them, Weiss and the guides called frantically to Kirk to return.

They jumped in the car and drove to where he was admiring the scenery, ushering him quickly inside. The military vehicle rolled silently past. Only once the Chinese were gone did the guides inform them of all the many laws they had just broken. Weiss was ready to go home.

Now hale and returned, he is still working on creating some 40 pots commissioned from the original he made on Everest, having raised over $6,000 for art school scholarships. He carried that pot and the one fashioned at 13,000 feet in “leatherhard” unfired condition across Tibet, into China, and back across the Pacific Ocean.

Only in the U.S. did anyone question it. Reentering the country, a customs agent asked Weiss what he had in that handmade cardboard box.

I said, ‘Oh, those are a couple of pottery pieces I threw on Mt. Everest,’” Weiss remembers with a smile.

“And the customs agent just looked at me and said, ‘Get out of here!’”

Article resources:

https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/world-record-for-making-a-pot-on-mt-everest#/