Late in September, on a hilly, sun-baked property at the foot of Sonoma Mountain, Vince and Jenny Trotter spent three days in the heat hand-shelling late summer beans, grown on a quarter acre patch of row crops surrounded by premium wine grapes. While workers in nearby vineyards harvested small fortunes’ worth of fruit, the Trotters and their three-year-old son, Evan, assembled a heap of dried Hutterite and Calypso beans—a payoff of perhaps a few hundred dollars for the family.

Growing fruits and vegetables is labor intensive and rarely a lucrative endeavor anywhere. Growing food crops in Sonoma County can seem more a labor of love, and a statement about biodiversity, than a business plan. Indeed, most contemporary farmers see the area’s hill country of rich soils, quiet oaks, and morning fog as a paradise for grapevines—a vision that has transformed much of Sonoma County into one of the most massive monocultures in California.

Farming grapes here makes sense. The climate is right, and the cost of land makes fine wine production one of the best ways to stay afloat. But moreover, Sonoma County is a great place to grow food. Historic persimmon, walnut, apple, and fig trees—their trunks gnarled by the decades—stand in fields and along bike paths throughout the county, relics of an agricultural history that has mostly, though not entirely, passed. More importantly for people like the Trotters, such trees are also living reminders that the region, in both soil and climate, remains favorable for many kinds of crops.

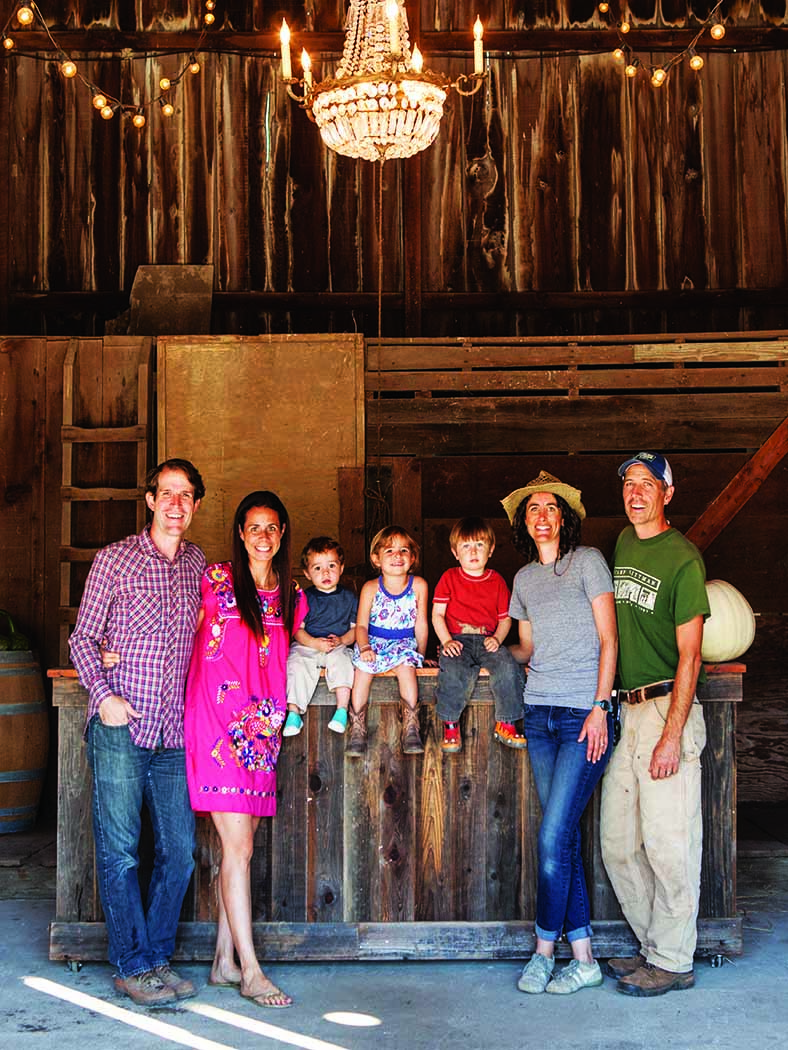

But the Trotters are working in tandem with another couple to make the region a little more hospitable for food production. The property’s owners, Nate and Lauren Belden, who have grown Pinot Noir, Syrah, and Chardonnay here under the name Belden Barns for 11 years, have partnered with the Trotters as part of a project to enhance the area’s cultural, culinary, and biological array while making room for growers not trained or invested in the niche lifestyle of winemaking. Farming food crops is not easy—especially in a place where land prices, driven by the homebuyer’s market and the wine industry, have skyrocketed.

Perhaps, the two couples say, it’s time to level the playing field.

“We made a goal that we would grow more than just grapes to highlight the diversity of agriculture and help give farmers a shot at making a living here,” Nate Belden says. “I think the wine industry has done a great job of romanticizing farming and how hard it is to make wine, but general vegetable farming is really hard. It’s hard to grow arugula consistently and to make cheese. While Sonoma County is one of the best places to learn about small-scale sustainable agriculture, it’s one of the harder places to actually get off the ground because it’s an expensive place to live.”

It's time to level the playing field.

The Beldens planted 120 fruit trees three years ago with the idea that a farming family would eventually take on the task of maintaining and harvesting them. With the Trotter family now onsite to do the farming, the partners envision a collaborative venture that is supported by three key pillars: Wine, vegetable and orchard crops, and the more technical crafts of cheese- and cider-making. The project, which plans to include a small creamery, is to be accompanied by the installation of a new tasting room.

With this infrastructure in place—water, land, equipment, and some of the marketing logistics—old-fashioned farming and cottage industry might prove to be lucrative.

Vince Trotter feels the history of such farming in Sonoma County has outlived, and will survive through, the predominance of grapevines. “There are many diverse family farms out here that are multi-generational,” he says. “That doesn’t just go away.”

What is different about the Trotters, though, is that they are first-generation farmers. They have tried farming where land is cheaper. They made a go at raising livestock and a variety of row crops, in tandem with a cottage-pickling outfit, in Nevada County in 2010. Later, they moved to coastal San Mateo County to work at Pie Ranch, a nonprofit educational farm that specializes in eggs, dairy, orchard fruits, and vegetables.

In 2012, the couple moved to Sonoma County to set down new roots. On the land they now share with the Beldens, the Trotters have planted sweet potatoes, corn, beans, squash, melons, and potatoes. Adjacent to the rows of crops are fruit trees like mandarins, lemons, pears, plums, and quince.

This first year of growing vegetables and watching the initial fruit crops ripen is serving as an evaluation period—for the farm and the people. “The fiscal arrangement isn’t fully defined yet,” Nate says about the agreement he and Lauren have created with the Trotters.

“This past year was a test run to see what may and may not work on our particular site, with us providing the land, equipment, and infrastructure, and the Trotters providing their expertise and a lot of hard work.”

Beans are doing well. So is corn, which will be milled into polenta. The quince is softball-sized and the lemon trees, though young, are bearing. The apples had a tough season after deer broke past the property’s perimeter fence and stripped the foliage.

The food is currently mostly being sold to friends. Next year, the plan is to push their produce into local restaurants and retail markets. Much of the focus will be on value-added products, like jams and preserves that have a longer shelf life.

“Cider is also going to be an important leg of the stool,” Nate says. “It will bring them more bang for their acreage.”

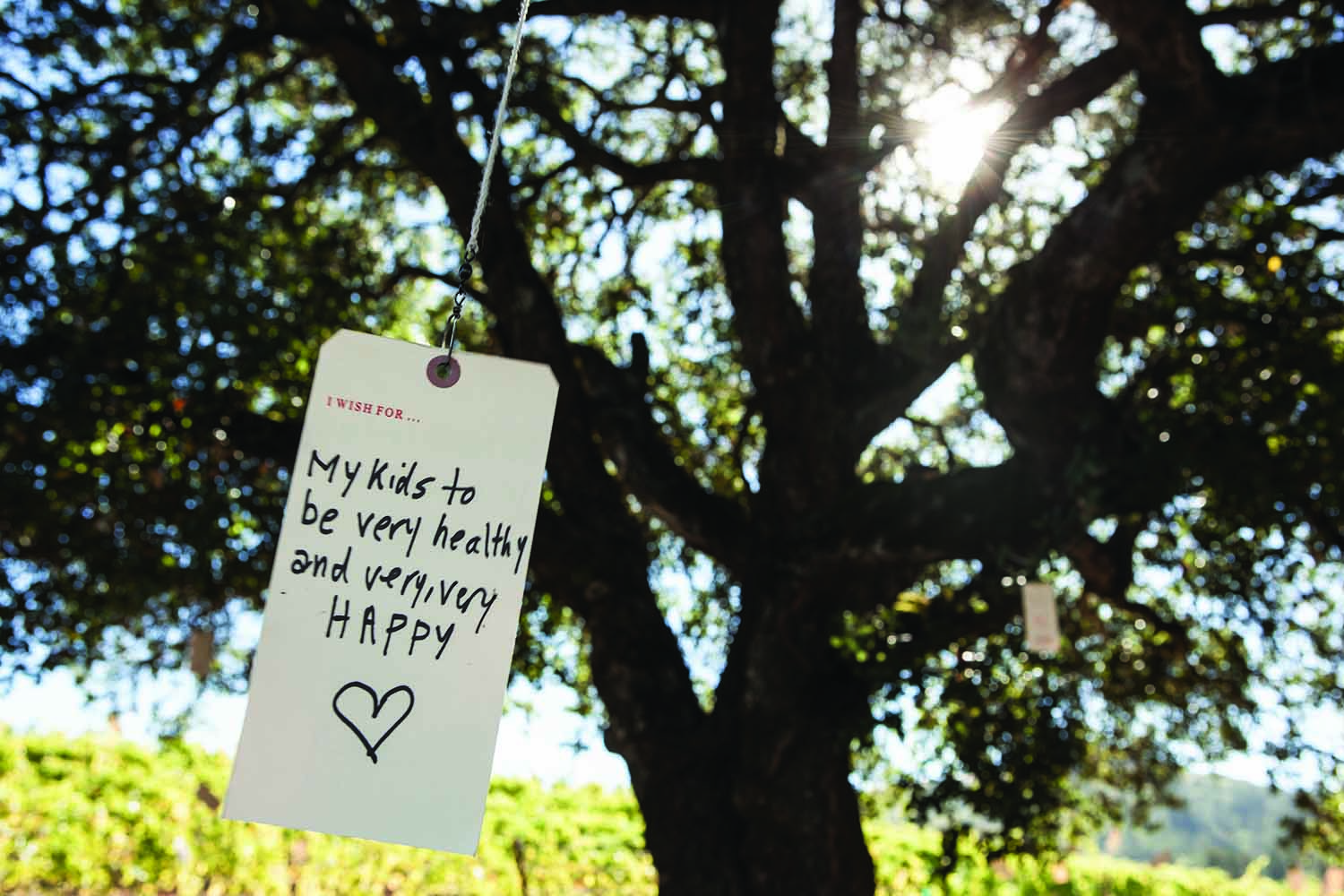

Cider is treated by taxing agencies like wine, meaning the apple juice can be fermented onsite. The partners also have plans to make farmstead cow cheese—and, Jenny Trotter adds hopefully, raise their children together.

“This isn’t just about having a business together,” she says, looking at Evan’s toys scattered among trowels, shovels, and buckets. “We’re raising families together.”

The Belden property is 55 acres, and the vineyards are rather small—totaling just 20 acres. The row crops and orchard could be expanded but will never occupy more than several acres. Water demands are modest, with the property’s small reservoir, filled each year by winter rain, holding enough water to provide for all agricultural needs. Even last year’s meager precipitation filled the pond to overflowing.

Still, a group of neighbors has sued to stop their project. The plaintiffs—Friends of Sonoma Mountain Road—filed a lawsuit last November against the county for approving the Beldens’ application to build a 10,000 case winery and a 10,000-pound-per-year cheese operation with less than 10 public events a year.

The unease is rooted in concerns about environmental impacts of new development in the area and the use of the winding, treacherous road up Sonoma Mountain for tourists.

Outreach to the plaintiffs’ attorney received no reply.

“There is definitely a knee-jerk reaction to the wine business right now,” Nate says, referring to many projects that have drawn fire in recent years from locals concerned about increased traffic, noise, and especially, water use. Sonoma County officials have historically been lenient toward winery projects. Only in recent years has this changed, with a series of proposals derailed by legal challenges from residents concerned about overuse of public water supplies, tree removal, and traffic.

Water, Nate says, is the stated reason for concern among the neighbors that have sued to stop his project. He feels the lawsuit is misguided. The property has a well, but Nate says they never use it as the reservoir meets all their needs. The new project, with its 120 trees, a field of annual crops, and a small cheese house will use as much water as a four-and-a-half bedroom house, he says.

He feels the plaintiffs in the lawsuit misunderstand the scope of the proposed project, which now cannot proceed until the partners conduct a lengthy environmental impact report under the California Environmental Quality Act.

“The cheese operation would fit in a trailer,” Nate says. “[Challenging it as being too large] is analogous to thinking that someone knitting gloves to sell on Etsy is the same as Levi’s building a huge clothes factory.” He adds that the proposed cheese operation is so undersized that, at maximum production rates, it would make in an entire year what the Laura Chenel chévre operation in Sonoma Valley makes in less than a week.

We’re raising families together. Jenny Trotter

Nate says the longer the legal proceedings go on, the more the opponents lose their vigor against the project, noting that some have come to visit and gone away positively impressed by the small scale of the farm and the tasting room, which will be based out of a barn fitted with a wooden counter and some stools.

The project will admittedly generate traffic, and water will be needed to grow and sustain operations. Still, the Beldens believe their partnership with the Trotters is much more than a private profit venture. It could, Nate says, help enhance the entire county. He envisions a North Bay food culture like that of Europe, where food production is as diversified as the landscape itself.

“I think there is a lot of value long-term in a sort of European model where you may be in this little village, and they make pickles a certain way, and that’s their pickles, and anyone who wants those pickles has to get them from that place,” Nate says. “I think that kind of approach could add to the charm of the North Bay. It would be really additive to have a reputation for making more than just wine.”

Article Resources: