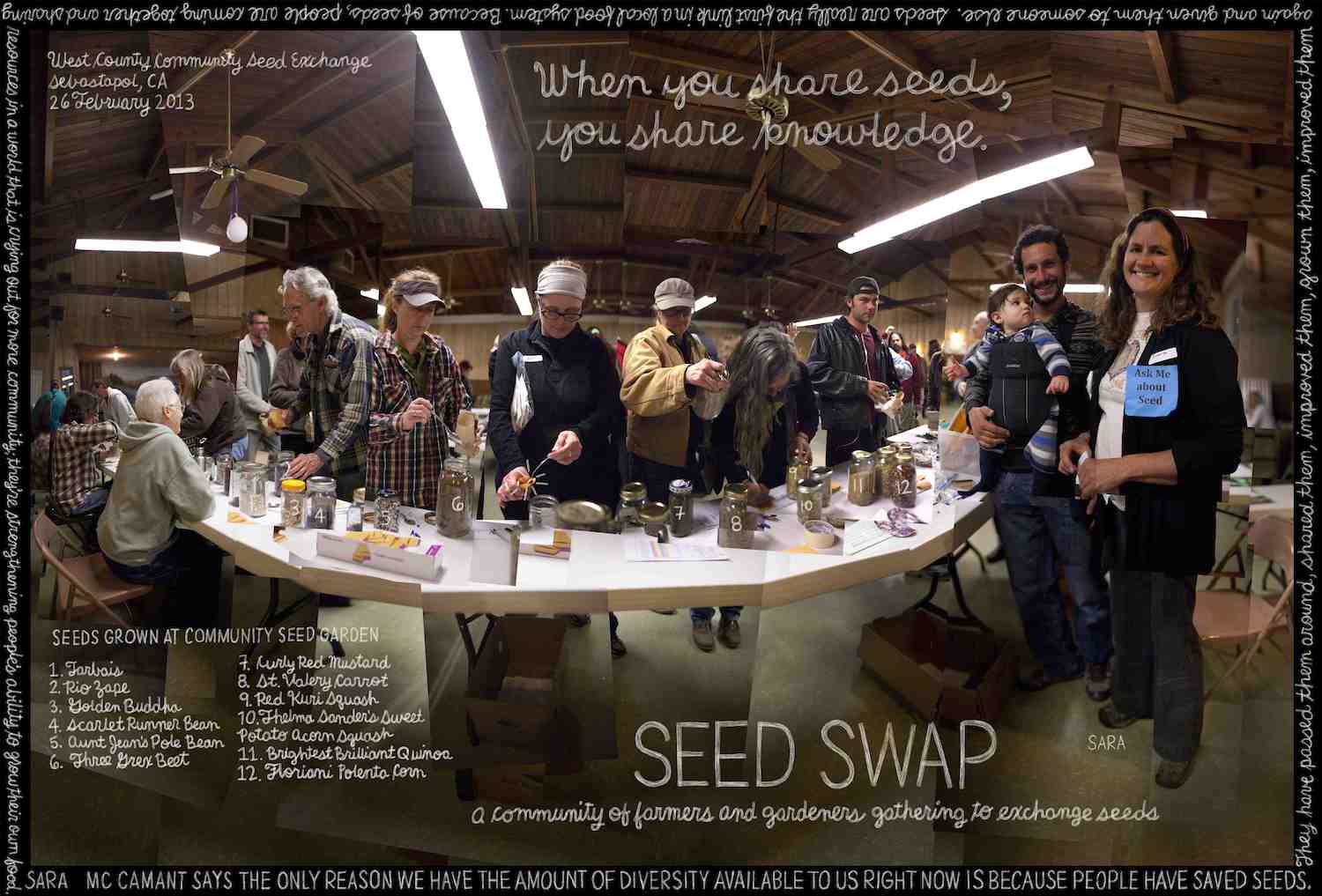

From a Sebastopol seed swap to the imprint of community.

Note: This is an adapted excerpt from Petaluma writer and artist Douglas Gayeton’s new book, Local: The New Face of Food and Farming in America (Harper Design, 2014; $35).

One moonless February night I walk through a freshly cut hay field in Sebastopol. My destination is a single incandescent bulb. It illuminates the front door of the Sebastopol Grange Hall. Inside this modest building people have gathered, their heads bowed in deep concentration over rows of folding tables. On each are clusters of carefully marked glass jars, which they inspect closely, even hold up to the light. After some consideration they may gently open their lids, take a sniff, then dip some of these precious contents into small envelopes that are thrust into their now-bulging pockets, but not before scribbling cryptic admonitions like “careful—a real climber” or “full sun only” or “must have drainage.”

This is a seed swap, and the people here have come to share seeds—and stories—before spring planting.

“The world is crying out for more community,” says Sara McCamant, cofounder of the West County Community Seed Exchange and organizer of tonight’s event. “People are coming together and sharing resources, learning what grows well from one another. We’re strengthening their ability to grow their own food, because when you share seeds you also share knowledge.”

In earlier times, seed swaps were a yearly occurrence in any farming community. Farmers grew plants, saved seeds from those that performed best that season—or tasted sweeter or produced more beautiful flowers—then replanted them the following year as the cycle of life repeated. These seeds were open-pollinated, meaning they were “true-to-type” and would produce plants just like their “parents” the following year. Over time, each successive generation adapted to its geography’s unique climate, temperature, soil, pests, and even plant viruses. Open-pollinated seeds were a cultural record. They store vital information about a community, passing it from one generation to the next. Civilizations rose or fell—and even went to war—depending on the success of these seeds.

In earlier times, seed swaps were a yearly occurrence in any farming community. Farmers grew plants, saved seeds from those that performed best that season—or tasted sweeter or produced more beautiful flowers—then replanted them the following year as the cycle of life repeated. These seeds were open-pollinated, meaning they were “true-to-type” and would produce plants just like their “parents” the following year. Over time, each successive generation adapted to its geography’s unique climate, temperature, soil, pests, and even plant viruses. Open-pollinated seeds were a cultural record. They store vital information about a community, passing it from one generation to the next. Civilizations rose or fell—and even went to war—depending on the success of these seeds.

“America’s founding fathers were ‘founding farmers’ who recognized that we lacked the appropriate seeds to feed a growing nation,” explains Matthew Dillon of Seed Matters, a nonprofit dedicated to organic seed preservation. He tells me stories about how Thomas Jefferson smuggled rice seeds out of Italy by sewing them into his coat lining, and how our earliest ambassadors were ordered to collect seeds from each port of call. “Seeds have been a public natural resource that has been shared among people for over 10,000 years,” he continues. “In our republic’s early days, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office even grew out seeds, documented their collections, and sent out letters to agricultural journals announcing their discoveries.” More important, they gave seeds away—more than a billion before the close of the 19th century. To hear Dillon tell it, spreading seeds was a patriotic act.

The story of how our seeds lost their innocence is both interesting and obvious. We evolved from an agricultural system based on biodiversity to an industrialized model that grows much less diverse crops. The antecendents of this shift date back to the 1920, when trade associations exerted enough leverage to radically curtail the USDA’s public seed program. The responsibility to breed and distribute seeds shifted to the private sector and land-grant university plant breeding programs, whose research primarily supports farmers and food processors.

Spreading seeds was a patriotic act.

During this period, plant breeders popularized the use of hybrid seeds by combining qualities from different plant varieties. These new hybrids produced perfectly uniform crops but their “false-to-type” seeds could not be saved. Farming quickly evolved from a diverse system to one of rotating monocultures, and since hybrid seeds could not be saved, the art of saving seeds at harvest and storing them until next spring’s planting nearly disappeared.

In 1980, passage of the University and Small Business Patent Procedures Act presented universities with a new challenge: instead of relying on federal grants, these institutions were now asked to find outside funding sources and to secure patents and royalties as additional sources for revenue.

Large seed companies are interested in technology advancements that boost their bottom line, which means their gene jockeys are more likely to focus on patentable breakthroughs related to the largest agricultural markets—corn and soy, for example—rather than breeding the tomatoes that will grow in the cool summer climate of Petaluma. And by focusing research on large crops, they can exert control over their commercial production.

As Micaela Colley of the Organic Seed Alliance points out, “When you invest all your effort into plant breeding being done by a few people, what you’re really investing in is breeding for the needs of a centralized food production model. We’re not advocating that every farmer needs to breed his or her own crops, but we believe in creating regional networks of farmers, seed companies, and university-based support, plus independent and public plant breeders that all work together to address the needs within a region.”